|

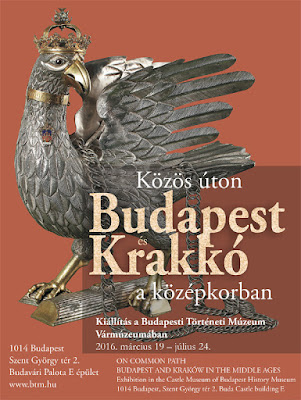

| Poster of the exhibition |

A new exhibition, titled On Common Path - Budapest and Kraków in the Middle Ages opened last week at the Budapest History Museum. It is the result of a common project of the Hungarian institution and the Historical Museum of the City Kraków, and was realized in the larger framework of the cooperation of Hungary and Poland, as the first step of the Hungarian Cultural Year in Poland.

The exhibition surveys the parallel histories of Buda and Kraków from the period of their foundations to the high points of their development in the late Middle Ages. Both towns were among the major cities of medieval Europe. The exhibition presents common events in the history of the town, as well as personalities who played an important role in the history of both towns. Among other things, it focuses on the Anjou and the Jagiellonian dynasties, as well as on Stephen Báthory, Prince of Transylvania and King of Poland. Through these historical figures, the exhibition illustrated that not only the two cities, but also the history of the two nations is closely linked. The last period surveyed is the 16th century, which represents a break, especially in the development of Buda, which came under Ottoman Turkish occupation in 1541.

Most of the objects in the exhibition give insight into the everyday life of city dwellers as well as into festive occasions. A large number of archaeological finds are presented, including many objects never before shown (expecially from Buda). The parallel histories of the two cities are installed on two sides of the exhibition rooms, while showcases placed in the center of the rooms features historical figures and institutions - such as the University of Cracow - which represented points of contact for the two towns.

|

| View of the exhibition - Buda (Photo: BTM - Bence Tihanyi) |

The exhibition will remain on view until July 24 in Budapest, and later will be presented in Kraków as well, It is accompanied by a detailed and useful exhibition catalogue, which will also be published in and English-language edition.

|

| View of the exhibition - Kraków (Photo: BTM - Bence Tihanyi) |

Exhibition: Közös úton - Budapest és Krakkó a középkorban. On Common Path - Budapest and Kraków in the Middle Ages. Castle Museum of Budapest History Museum, March 19 - July 24, 2016. The poster, seen above, features the emblem of the Krakow Rifle Association, the "Rooster Company," a work of Gian Giacopo Caraglio from 1564/65. Krakow, Museum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa.

|

| Photo: Nol.hu |

Catalogue: Közös úton. Budapest és Krakkó a középkorban. Kiállítási katalógus. Ed. Judit Benda, Virág Kiss, Grazyna Lihonczak-Nurek, Károly Magyar. Budapest, 2016, 335 pp.

|

| Martin Kober's portrait of Stephen Báthory from Kraków, 1583 |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)