After several years of preparation, a new book dedicated to the Art of Medieval Hungary was finally published by Viella in Rome. Edited and written by a team of Hungarian and international experts, including today’s foremost experts in medieval art history, the book provides an up-to-date overview of research about the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. The editors are Xavier Barral i Altet, professor of art history at Université de Rennes, Pál Lővei, researcher at the Art History Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Vinni Lucherini, professor of art history at Università di Napoli Federico II, and Imre Takács, Head of the Art History Department at ELTE.

The editors have developed a novel concept for this collection of studies: rather than providing a simple chronological structure, the first part of the book consists of a series of studies arranged into thematic groups, surveying medieval art in various contexts: the art of towns and villages, art in the context of liturgy and religious cults, and art in various public and private contexts. A great attention is also given to the sources and the historiography of medieval art in Hungary. The second part of the book contains two sets of shorter essays: one dedicated to key monuments and medieval artworks, while the second set deals with museums and collections of medieval art.

Publication of the book was coordinated by the Hungarian Academy in Rome, and especially its previous director, Antal Molnár. As stated in the publisher's description: "the Hungarian Academy of Rome offers to the medievalist community a thematic synthesis about Hungarian medieval art, reconstructing, in a European perspective, more than four hundred years of artistic production in a country located right at the heart of Europe. The book presents an up-to-date view from the Romanesque through Late Gothic up to the beginning of the Renaissance, with an emphasis on the artistic relations that evolved between Hungary and other European territories, such as the Capetian Kingdom, the Italian Peninsula and the German Empire. Situated at the meeting point between the Mediterranean regions, the lands ruled by the courts of Europe west of the Alps and the territories of the Byzantine (later Ottoman) Empire, Hungary boasts an artistic heritage that is one of the most original features of our common European past." In addition, the book was produced under the auspicies of the Research Centre for the Humanities of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and with the support of the National Bank of Hungary.

Thanks to the expertly written essays, as well as the exhaustive bibliography included in the volume, the book can be regarded as an essential new starting point for research on art in medieval Hungary. The detailed contents are listed on the publisher's website, and I copied them below as well. I case you are wondering, I contributed a study on village architecture, specifically on the art and architecture of parish churches in Hungary, as well as a shorter essay on the former Augustinian church of Siklós. I included one of my illustrations below.

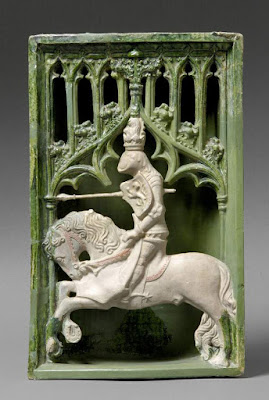

| Plates from the book |

The Art of Medieval Hungary. edited by Xavier Barral i Altet, Pál Lővei, Vinni Lucherini, Imre Takács. Bibliotheca Academiae Hungariae - Roma. Studia, 7. Roma: Viella, 2018.

732 pages, 176 plates, ISBN: 9788867286614

The book is now available for purchase.

From the contents - List of studies in the book

- Xavier Barral i Altet, Introduction. Hungarian Medieval Art from a European Point of View

- I. Sources and Studies for Hungarian Medieval Art

Ernő Marosi, Two Centuries of Research, from the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy to the Present

Kornél Szovák, Written Sources on Hungarian Medieval Art History - II. City and Territory

Katalin Szende, Towns and Urban Networks in the Carpathian Basin between the Eleventh and the Early Sixteenth Centuries

Pál Lővei, Urban Architecture

Zsombor Jékely, Expansion to the Countryside: Rural Architecture in Medieval Hungary

István Feld, Castles, Mansions, and Manor Houses in Medieval Hungary - III. Architecture and Art in the Context of Liturgy

Béla Zsolt Szakács, Romanesque Architecture: Abbeys and Cathedrals

Krisztina Havasi, Romanesque Sculpture in Medieval Hungary

Imre Takács, The First Century of Gothic in Hungary

Pál Lővei, Imre Takács, “Hungarian Trecento”: Art in the Angevin Era

Gábor Endrődi, Winged Altarpieces in Medieval Hungary - IV. Religious Cults and Symbols of Power

Gábor Klaniczay, The Cult of the Saints and their Artistic Representation in Recent Hungarian Historiography

Vinni Lucherini, The Artistic Visualization of the Concept of Kingship in Angevin Hungary

Pál Lővei, Epigraphy and Tomb Sculpture - V. Forms of Art between Public and Private Use

Evelin Wetter, Precious Metalwork and Textile Treasures in Late Medieval Hungary

Anna Boreczky, Book Culture in Medieval Hungary - VI. The Middle Ages after the Middle Ages

Imre Takács, Medieval Twilight or Early Modern Dawn: Art in the Era of Sigismund of Luxembourg

Árpád Mikó, A Renaissance Dream: Arts in the Court of King Matthias

Gábor György Papp, Medievalism in Nineteenth-Century Hungarian Architecture - Annex I. Medieval Artworks and Monuments

- Annex II. Museums and Collections Holding Medieval Art

| Siklós, Augustinian church. Detail of the early 15th-century wall paintings |