|

| Detail of one of the reliquary plaques |

It is well-known that the majority of the medieval monuments of the Hungarian Great Plains had been destroyed, primarily during the Ottoman Period. However, the territory had already suffered a major trauma before that: the Mongol invasion of 1241. Already at that time, entire settlements were destroyed and many of these locations were never rebuilt in later centuries. One such place was the medieval town of Péteri. The town was located near present-day Bugac, just south of Kecskemét, on the Kiskunság plains between the Danube at Tisza rivers. It was established possibly as a royal foundation in 1050 and developed quickly during the next two centuries. Around 1130-1140, members of the Becse-Gergely clan established a monastery there, which likely contributed to the development of the town. Pétermonostora was first mentioned in 1219. In the Spring of 1241, the town was overrun by the Mongols of Batu Khan and the site seems to have been abandoned after that. Recent excavations have brought to light evidence of the massacre of the town's population. Sometime after the Mongol invasion, Cumans were settled in the area - who used the ruins as a convenient quarry.

|

| The site of the monastery |

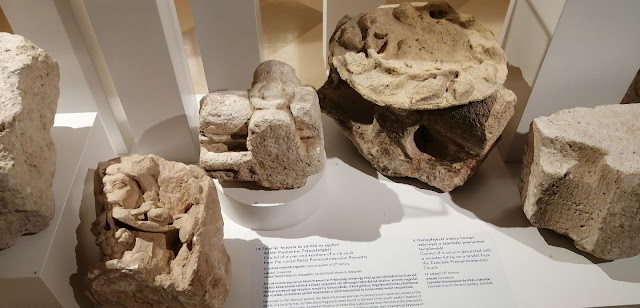

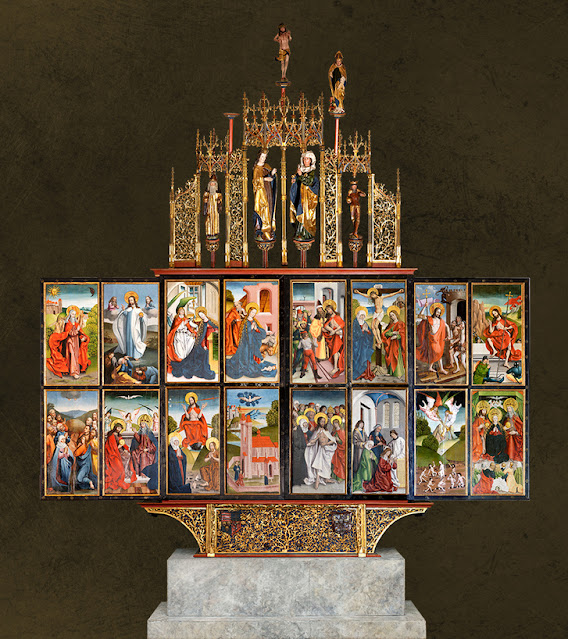

Excavations of the area lead by Szabolcs Rosta since 2011 have brought to light the remains of the medieval monastery of Péteri or Pétermonostora. A large, three-aisled basilica was discovered here, along with various monastery buildings. Remarkably, the ruins preserved a large number of important liturgical objects from the church. Along with the ongoing excavations of the nearby cemetery and the remains of the town itself, Péteri by now has become an extraordinarily rich source of Árpád-period material objects. The most famous objects come from the monastery church itself: among several smaller enamel reliefs from Limoges, the most important finds are two enamel plaques, which originally must have decorated a reliquary. Based on its iconography - the scenes show the Washing of the Feet, Christ talking to St. Peter, and the Ascension of Christ - the reliquary must have preserved the relics of the patron saint of the church, St. Peter. The enamel plaques were made in the Rhine region, around 1180. They are kept at the Katona József Museum in Kecskemét, and an interactive feature developed by Pazirik Ltd. gives a very useful overview of them.

|

| Enamel plaques from Pétermonostora |

Another extraordinary find came to light in 2018: it is a book cover made of bone, with figures of the evangelists and inlaid rock crystal decoration. Here are some pictures, along with some other pieces from several hundred finds:

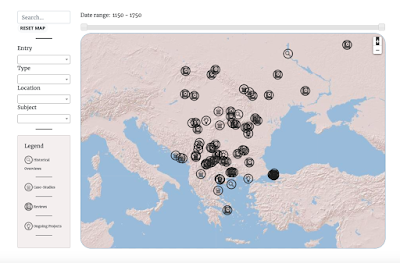

Excavations of the medieval town of Péteri and its monastery dedicated to St. Peter will likely continue in the coming years and will undoubtedly shed more light on the flourishing life of the Hungarian Great Plains in the decades before the Mongol invasion. To get more information on the site, have a look at this study of Szabolcs Rosta or this very useful 2017 overview by Edit Sárosi or watch a short film focusing on the site and on the restoration of the reliquary plaques (2020, in Hungarian). Pétermonostora is part of the Central European Via Benedictina network.