Imre Takács:

The Arrival of French Gothic in Hungary. Bibliotheca Collegii Professorum Hungarorum. Piliscsaba: Makovecz Campus Alapítvány, 2024.

ISBN: 9786150202501

Imre Takács's important book about the arrival of French Gothic art in the Kingdom of Hungary has recently been published in an English translation. The book is key to understanding the early reception of the new gothic forms in a far-away Kingdom of medieval Europe. It is well-known that Hungary was among the first places to embrace the new style, but the circumstances and the exact nature of the 'French connection' have been imperfectly understood. Takács provides not only an overview of these questions but numerous new observations and explanations. In historiography, a key role was accorded to the travel of Villard de Honnecourt. A 13th-century French-language codex in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris preserved the architectural and other drawings of Villard de Honnecourt, and this work has long fascinated scholars of the Gothic period (BNF Fr 19093). In the codex, Villard wrote the following next to a drawing of the traceried window of the cathedral in Reims: "I was sent to Hungary when I drew this, because it pleased me most" (fol. 10v). Additional passages also refer to his Hungarian trip.

|

This later inscription in the sketchbook of Villard states:

"de Honnecor[t], who had been in Hungary" (BNF) |

Imre Henszlmann, one of the pioneering Hungarian researchers of Gothic architecture, was among the first to recognize the significance of entries in the then-unpublished (but already known) codex. Like his contemporaries, he started out believing that Gothic was a German style. In 1846, he authored the first Hungarian monograph on medieval architecture, titled The Old German-Style Churches of Kassa (now Košice). During his study trip to England and France in the years following the War of Independence of 1848-49, Henszlmann became acquainted with French Gothic architecture and noted Villard de Honnecourt's sketchbook. In 1857, he presented his theory in Paris, proposing that Villard had designed none other than the Church of St. Elizabeth in Kassa (Košice) around 1270, during the reign of King Stephen V. While Henszlmann acknowledged that the cathedral in Kassa was ultimately built in a 'German' style, he argued that its foundational plan was distinctly French. This marked the beginning of scholarly investigations into the connections between French Gothic centers and Hungary. Though Henszlmann and subsequent scholars were incorrect about Villard de Honnecourt's role in Hungary, the question continued to resurface over time. A deeper understanding of the emergence of French Gothic in Hungary only became possible after significant archaeological excavations in the 20th century—most notably at the Castle Hill in Esztergom during the 1930s and at the Cistercian Abbey of Pilis in the 1970s. These excavations uncovered key monuments that shed new light on the spread of Gothic architecture in Hungary.

|

| Esztergom, Chapel of the Royal Palace, 1180s |

Ernő Marosi was the first to comprehensively analyze the origins of Hungarian Gothic architecture in his influential 1984 monograph, Die Anfänge der Gotik in Ungarn. The work focuses on the late 12th-century buildings of Esztergom and highlights the palace chapel there as perhaps the earliest example of the reception of northern French Gothic architectural innovations east of the Rhine. Marosi's insights served as the foundation for Imre Takács' subsequent research, and it is fitting that Takács dedicated his own work to his late professor, who passed away in 2021. Takács' scholarship represents the culmination of decades of research. It began in the 1990s when, as a curator of the Hungarian National Gallery, he reconstructed the tomb of Queen Gertrude—discovered at Pilis Abbey—using fragments excavated by László Gerevich and preserved in the Gallery. Takács then extended his efforts to a detailed study of the complete carved material from Pilis Abbey and the stone collection of the Castle Museum in Esztergom. Among the fragments in Esztergom, the Porta Speciosa, the former western gate of the cathedral, became a particular focus of his research, leading to his recent publication on the subject. The third major site of Takács' research was Pannonhalma Abbey, where he played a key role as the main organizer of the exhibition celebrating the abbey's 1000th anniversary. He also served as the editor of the comprehensive three-volume catalog published for the occasion in 1996.

|

| Esztergom, Deesis-tympanum, originally on the inside of the Porta Speciosa of the Cathedral |

These three sites also feature prominently in the new monograph,

The Arrival of French Gothic in Hungary, published this year. The English-language volume is a translation of Imre Takács' 2018 monograph in Hungarian, which came out with the title

The Reception of French Gothic in Hungary in the Age of Andrew II. The slightly broader English title is justified by the fact that the buildings of Esztergom in the time of Béla III also play a major role in the volume.

At the heart of the monograph is the recognition that in some of the central sites of the Kingdom of Hungary, the structural and formal solutions of French Gothic art appeared much earlier than in other countries of Europe. Imre Takács shows that this is true not only for the time of Béla III and the early Gothic period but also for the time of King Andrew II and the Classical Gothic period, which was fashionable at the time. In addition to Esztergom, Pilis, and Pannonhalma, several important buildings of the early 13th century are mentioned in the text: the cathedral of Kalocsa, the Premonstratensian abbey church of Ócsa, the Cistercian abbey of Topuszkó, etc. Along with goldsmith works, the monograph discusses all the most important surviving evidence of courtly art of the period.The detailed discussion of the topic begins with the art of the time of Béla III, primarily with the study of the early Gothic elements of the royal palace and the cathedral of Esztergom. It is here that the use of the red marble from the Gerecse hills, which played a major role in the Gothic period, first appeared in Hungary. Takács describes in detail the most important monuments, especially the Porta Speciosa, the main gate of the cathedral, decorated with colored marble decoration. This monument, dating from the end of the 12th century, is contemporary with the first Gothic monuments built in Esztergom, above all the palace chapel. Takács dates this building campaign to the second half of the 1180s and links the appearance of the 'French connection' to the arrival of Queen Margaret of Capet in Hungary in 1186. This construction coincided with the building of the Cistercian priory of Pilis, founded by Béla III in 1184, which is the subject of Takács's next chapter. Construction there lasted until the first decade of the 13th century, after which the French-educated masons who worked there were employed on two important buildings of the period of Andrew II: the new building of the cathedral of Kalocsa, begun around 1210 by Archbishop Bertold of Andechs-Meran, and the Premonstratensian church of Ócsa, built a little earlier (but never fully completed). This chapter describes in detail how Gothic forms spread throughout the Kingdom of Hungary in the decades before the Mongol invasion of 1241, with the cloisters of the royal residence in Óbuda, the abbey of Somogyvár, and Szermonostor as the most important additional examples.

|

| Pannonhalma, abbey church, vaulting of the nave |

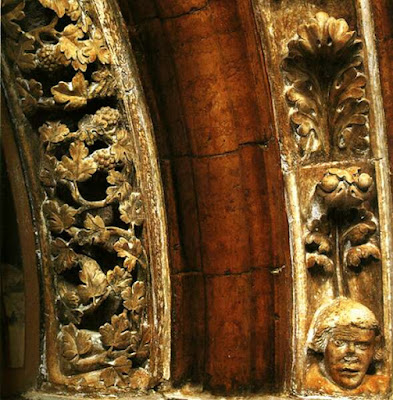

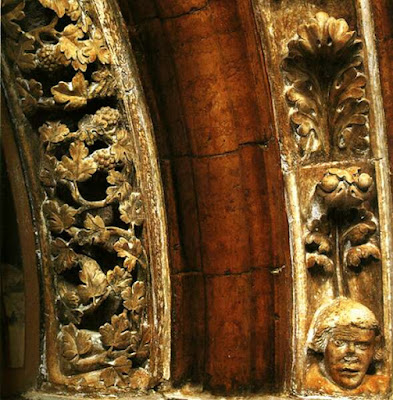

The fourth part of the volume deals with the most remarkable phenomena from an international point of view: when the French Classical Gothic forms, which were considered modern in their home country, appeared in Hungary in the 1220s. In this respect, Hungary is no longer as unique as it was at the time of the reception of early Gothic in the late 12th century, since the stone carvers and sculptors who set out from the cathedral lodges of the great French cathedrals appeared in several parts of the Holy Roman Empire, such as in Strassburg or Bamberg, as well as in Klosterneuburg near Vienna. In Hungary, one of the key monuments of this phase is the completion of the Benedictine abbey church in Pannonhalma, especially the upper parts of the southern nave wall completed for the consecration in 1224, and the construction of the Porta Speciosa, which is incorporated into this wall. Imre Takács provides detailed evidence of the direct Reims origin of the carvings found here. The conclusions concerning the presence of Reims stone carvers in Hungary before 1224 are of great importance: the date of the consecration in Pannonhalma also allows the rather uncertain chronology of the Reims cathedral at that time to be clarified.

|

| Detail of the Porta Speciosa at Pannonhalma |

In the next section, Takács describes in detail the most important sculptural monument of the period, the fragments of the tomb of Queen Gertrude, who was murdered in 1213. He also shows that the sculptor of these carvings came to the Kingdom of Hungary from the building lodge working on the cathedral in Reims. In this context, the fact that Villard de Honnecourt, who compiled the best-known collection of architectural drawings of the period, also left for Hungary from Reims, around 1220 according to most scholars, is particularly noteworthy. Political connections also explain the links: in particular the family circle of Yolande Courtenay, second wife of Andrew II. A red marble tomb slab with engraved decoration, also found in the abbey church of Pilis, is linked to a member of this family. The style of the tomb is exactly the same as the drawings in Villard de Honnecourt's sketchbook. The final part of the book studies objects of the minor arts, mainly in the field of goldsmith works, which have also occupied the author since the beginning of his career: the seals of the Árpád monarchs, and the analysis of a special 13th-century technique of luxury goldsmith decoration, the so-called opus duplex.

|

Fragment of a seated figure from the sarcophagus of Queen Gertrude,

originally from Pilis Abbey (Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

|

All these observations highlight the direct link that existed between the Hungarian royal court and the contemporary centers of French Gothic. The monuments that are given shorter passages in the text, sometimes with only one or two carvings representing French Gothic forms, indicate that the most modern architectural forms were widespread in Hungary in the pre-Mongol period. As we have seen, the question is of great importance not only for the spread of Gothic art in Central Europe but also for a more accurate chronology of French monuments. We can only hope that some of the archaeological research currently underway, especially the excavation of the Cistercian monastery at Egres, which served as the burial site of Andrew II and his wife Yolande, may add further finds to the picture of French art of the period painted by Imre Takács.

|

Golden seal of King Andrew II

|

At this point, it is worth highlighting the research topics of Imre Takács, who has been teaching at the Institute of Art History at ELTE since 2016. In addition to the subjects explored in this volume, which have accompanied his academic career, two additional areas of his research deserve special mention. First, he has extensively studied the history of the construction and carvings of the Gyulafehérvár Cathedral, the only surviving Árpád-era cathedral. Second, he has focused on Hungarian royal monuments, particularly artworks associated with King Sigismund. Takács has written on these topics in

The Art of Medieval Hungary, a book co-edited by him and published in English in Rome in 2018. The Rome volume aimed to make the lesser-known material on medieval Hungarian art accessible to the international scholarly community in a clear and structured handbook. It includes a summary of the first century of Hungarian Gothic art, which briefly introduces many of the research findings elaborated in detail in the current monograph. Finally, these findings are presented here in detail and in English.

Just as Ernő Marosi's book marked a pivotal moment in the international recognition of Hungarian Gothic art, the publication of Takács' detailed monograph in English is poised to play a similarly significant role in advancing the study of the spread of French Gothic in Europe. Overviews of European Gothic art can now be enriched with new insights into the contributions of the sculptors from Reims who worked in Central Europe, especially in Hungary, including their achievements in Pannonhalma (recent publications often ignored these connections). The monograph also contributes to a clearer interpretation of the Villard de Honnecourt question. For these reasons, the availability of a major synthesis of Imre Takács' scholarly achievements in the language of international scholarship is both very welcome and of great importance.

Finally, a word about the excellent and high-quality production of this elegant hardcover volume. The book is presented in a different format from the Hungarian edition, featuring 536 pages and 676 high-quality illustrations seamlessly integrated into the text. The way the black-and-white illustrations accompany the text significantly enhances the readability of the volume (a major improvement compared to the Hungarian edition). It should also be noted that the book has been translated by Alan Campbell with exceptional precision and a high linguistic standard. It surely belongs to the shelf of all serious scholars of the Gothic!

In Hungary, the book can currently be purchased at the bookstore of ELTE. It is also possible to contact the publisher, Collegium Professorum Hungarorum (Makovecz Campus Alapítvány) for further information.