Lino Pertile, the director of Villa I Tatti (The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Florence), as well as Assistant Director Jonathan Nelson are in Budapest these days. Villa I Tatti has had very close connections with Hungary - generally every year they had at least one Fellow from Hungary. This connection is also reflected in the research interests at I Tatti - the Italian (especially Florentine) connections of Hungarian Humanism and early Renaissance art have always been in strong focus. This connection resulted last year in the publication of the book titled Italy and Hungary - Humanism and Art in the Early Renaissance (see my review here). The book will be presented tomorrow at the Budapest History Museum.

While the presentation of the book is clearly one of the main reasons of the visit of I Tatti's directors, they are both giving lectures while here. Lino Pertile gave a lecture in the framework of the Medieval Afternoon at the Central European University, while Jonathan Nelson will give a lecture about 15th century Florentine painters at the Art History Department of ELTE tomorrow. Hopefully these events will further strengthen the ties of Villa I Tatti to Hungary.

Oh, and what else happened at CEU's Medieval Afternoon? The event marked the inauguration of CEU Medieval Radio, which you can find and listen to here.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Martin and Georg of Klausenburg

|

| Martin and Georg of Klausenburg: St. George Prague, National Gallery |

I haven't had a lot of time to update my blog recently - but I thought I would post this for St. George's day. The image above depicts what may be the most beautiful statue made in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Made by the brothers Martin and Georg of Klausenburg (Kolozsvár / Cluj) in 1373, the statue is the only surviving work from the production of their bronze workshop. Their other works - bronze statues of the Hungarian kings St. Stephen, Prince St. Emeric and St. Ladislas, as well as a large equestrian statue of St. Ladislas (all of these at Várad / Oradea) all got destroyed during the Ottoman wars, after the capture of Várad in 1660. The statue of St. George has been in Prague at least since the 16th century - but it is not known when and how exactly it got there. It is regarded as the first free-standing monumental bronze equestrian statue since antiquity. Information about its makers and the date was preserved on the now-lost shield (and is known from 18th century transcriptions):

Today, a copy of the statue is still standing in the third courtyard of Prague Castle, near the cathedral of St. Vitus. The original has been in the National Gallery in Prague since the 1960s.

A lot has been written on the statue in recent years, especially in a series of articles published in the Bohemian art history journal Umeni. See in particular the studies of Klara Benesovska and Ivo Hlobil from 2007, or the study of Ernő Marosi published in the 1999 volume of the journal. The connections of the bronze statue to the art of Trecento Italy (especially the Cathedral of Orvieto), the naturalism of some of its details, the historical context of the statue as well as its connections to other works by the brothers are all topics worthy of even further investigation.

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Medieval castle of Krasznahorka burned down

In a tragic event today, the medieval castle of Krasznahorka (Krásna Horka, Slovakia) completely burned out today. The roof of the castle caught fire, and the fire spread to all areas of the castle, burning all the roofs - and, presumably, everything under them. Firefighters battled the blazes for several hours, and finally managed to stop the fire, but the castle is still engulfed in smoke. There are no reports yet of damage to the artworks and other objects in the castle - but it is no doubt very serious. The cause of the fire has not yet been established.

|

| Krasznahorka castle, before the fire |

Krasznahorka, located near Rozsnyó (Rožňava) in south-eastern Slovakia, just north of the Hungarian border, was one of the most intact medieval castles of Upper Hungary, built by the Bebek family and later owned for centuries by the Andrássy family. You can read about the history of the castle on the official website. Krasznahorka managed to escape war damage both during the Turkish wars and later, in WWII. It burned down only once before, in 1817. The castle has been operated as a family museum and mausoleum since about the mid-19th century. Exhibitions inside the castle included valuable paintings, furniture and weapons. One of the large bastions has been turned into a Baroque chapel - famously holding the mummy of Zsófia Serédy, the wife of István Andrássy. Photos taken after the fire show that the roof of the chapel also burned down.

Here is a video of the fire, and a photo taken after the fire was put out - both showing the scale of devastation. Krasznahorka looms large in both Hungarian and Slovak historical consciousness - a joint effort will be needed to rebuilt what has been lost today.

Update on March 11th: Preliminary reports after the fire claim that most of the exhibitions and historic objects survived the disaster. Although all the roof structures of the castle burned in the fire, the vaults did not collapse - thus the historic interiors were not completely destroyed. Objects are now gathered in safe areas inside the castle. Obviously, only a detailed survey and inventory can reveal the extent of the damage in the end. So far, no photos of the interior after the blaze have been published.

Sunday, March 04, 2012

Niclaus Gerhaert at the Liebieghaus

|

| Niclaus Gerhaert: Self portrait (?), c 1463 Musée de l'Oeuvre Notre-Dame, Strasbourg |

The Liebieghaus in Frankfurt dedicated a monographic exhibition to the late Gothic sculptor Niclaus Gerhaert of Leiden. Alongside Hans Multscher, Gerhaert is regarded as the most important artistic character developing the naturalistic formal language of Late Gothic sculpture. His career corresponds to the spread of artistic ideas from west to east: although it is not known whether he was actually born in Leiden (given as his origin in later sources), but he was likely trained in the artistic milieu of the Southern Netherlands, then in the 1460s worked on the eastern part of the Holy Roman Empire - more precisely in Strassburg - and was finally invited by Emperor Frederick III to Vienna and Wiener Neustadt, where he died in 1473. Although the corpus of works firmly attributed to him is rather small, his influence was enormous, and members of his workshop as well as his followers determined the development of Late Gothic sculpture in Central Europe. The art of both Veit Stoss and Tilman Riemenschneider would be unthinkable without the influence of Gerhaert.

The exhibition currently on view in Frankfurt is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue edited by Stefan Roller. There are essays in the catalogue by a number of authors, following an introductory study by Roland Recht. This part is followed by catalogue entries, the first part of which include all the surviving works attributed to Niclaus Gerhaert (including those not in the exhibition), while the second part analyses the sculptures featured at the Frankfurt exhibition - arranged in groups of works from the environment of the master, and works showing his influence.

In the following, I would like to focus on one aspect of the subject, the influence of Gerhaert in the Kingdom of Hungary. I stated above that the sculptor was invited to Vienna by Frederick III, the most formidable opponent of Hungary's king Matthias. Gerhaert was commissioned to work on the tomb of the Emperor (in the Stephansdom of Vienna) and also on that of Queen Eleonore of Portugal (in Wiener Neustadt). Work on the Vienna tomb was likely disrupted in 1473, at the death of the artist, and again in 1485, when the troops of Matthias moved in to occupy the town. By that time the tombstone was moved to Wiener Neustadt, only to be returned to Vienna in 1493, so three years after the death of King Matthias. The tomb was not completed until 1513. There are few other works firmly attributed to Gerhaert from his Viennese period: first among them is the tomb of Queen Eleonore at Wiener Neustadt, wife of Frederick III, who passed away in 1467 - at the time the master was invited by the Emperor. In Wiener Neustadt, there is also a painted limestone statue of the Man of Sorrows at the former Cathedral (the Diocese was established by Frederick in 1469). Apart from these stone monuments, there a few wooden statues from this period, as Niclaus Gerhaert was an equally versatile sculptor both in stone and wood. Two small statues of the Virgin in Child - one in the Metropolitan Museum, the other in private collection - round out this period of the artist.

| Head of St. John from Tájó |

In the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary, it was his works of wood which exerted a considerable influence. Stefan Roller dedicated a study to the influence of of Gerhaert in Central Europe, and two objects from Upper Hungary (the territory of modern Slovakia) are actually included in the exhibition. Altogether, four works are discussed: the Head of St. John the Baptist from Tájó (Tajov, Slovakia), the main altar of Kassa (Košice) and the Nativity group as well as a figure of the Virgin at the reading stand - both originally from the main altar of the parish church of Pozsony (Bratislava).

Sunday, February 19, 2012

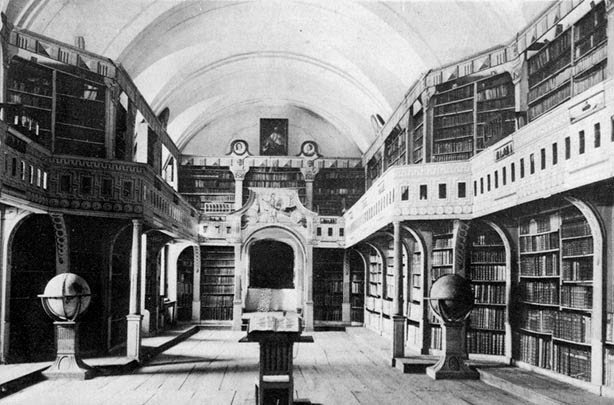

Medieval manuscripts of Batthyáneum available online

The Batthyáneum Library of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia, Romania) is one of the most important historic libraries in Transylvania. It was founded in 1798 by Ignác Batthyány, the bishop of Transylvania. The library was housed in the former church of the Trinitarian order - first an observatory was created here, and later the library was established in the building (all this was modeled on the Archdiocesan Library of Eger). The library of Batthyány grew from many sources, but the most important among these was the library of Christoph Anton von Migazzi, the bishop of Vác and also the bishop of Vienna. Batthyány bought the 8000 volume library of Migazzi, which included a lot of medieval manuscripts. When established at Gyulafehérvár, the Batthyáneum held about 20.000 volumes - a number which continued to increase throughout the 19th century. In addition to simply being a library, the institution worked as a museum, holding Batthyány's collection of minerals and naturalia, as well as a collection of ecclesiastical art. Finds from the excavations of Gyulafehérvár cathedral carried out by Béla Pósta in the early 20th century are also kept here.

The 20th century history of the library was not free from controversy: some books were sold in the 1930s, but the institution continued too function as a public library even after the Trianon peace treaty awarded Transylvania to Romania. However, in 1949 the collection was nationalized, and later became part of the Romanian National Library. Access to the collections became very limited - a situation which continues to this day. Even though a government decree returned the building and collection of the library to the Roman Catholic Archbishopric of Gyulafehérvár, the Library still functions as part of the state library system, and the court cases going on have so far not clarified the situation.

The library holds today altoghether 927 manuscripts and 565 incunabula, making it the richest collection of this kind of material in all of Romania. The medieval manuscripts are of various origins: Migazzi's library included all kinds of western manuscripts, but Batthyány also bought complete medieval libraries from Hungary, including the holdings of the ecclesiastical libraries of Lőcse (Levoča / Leutschau, Slovakia, see this Hungarian language study with German summary: Eva Selecká Mârza: A középkori Lőcsei Könyvtár, Szeged, 1997.). Several Transylvanian collections were also incorporated into the library, and there are rich holdings of orthodox Romanian manuscripts in the collection. In the framework of a European digitization project, a large number of manuscript are now available in the Manuscriptorium platform. In fact, there is a special section dedicated to manuscripts from the Batthyáneum.

The library holds a large number of first class illuminated manuscripts - many of which can now be consulted online. The following is a selection of a few of the most important of these (providing direct links to pages of this dynamic website is quite complicated. I managed to make direct links to the digital facsimile pages below - but you may start to browse or search from the start page, to get to object descriptions, etc.)

Ms II 1, first part of the Lorsch Gospels (Codex Aureus of Lorsch), from the Palace workshop of Charlemagne, dating around 810 (on the history of the whole manuscript, see also this overview)

Ms III 87, a nicely illustrated early 15th century Franco-Flemish Book of Hours

Ms II 134, A Missal from Pozsony (Bratislava / Pressburg), dating from 1377, with explicit by Henrik of Csukárd

There is a lot more there - you can start browsing from the start page, Manoscriti qui in theca batthyanyana. Furthermore, you can find some more illuminated manuscripts from the Europeana database - not all of which have been made available in the current digitization effort.

Sunday, February 05, 2012

'Apollonius pictus' facsimile published by National Széchényi Library

The oldest medieval manuscript of the National Széchényi Library is a fragment, which has recently been identified (COD. Lat. 4). It contains a late-antique "adventure novel" of the story of King Apollonius of Tyre. The novel enjoyed great popularity in the Middle Ages. The manuscript contains not just the text of the novel, but 38 uncolored pen drawings, making it the oldest illustrated copy of the story. Despite the importance of the manuscript, it has been almost completely unknown.

The parchment manuscript was written around the year 1000, in the Benedictine monastery of Werden an der Ruhr, situated in the archdiocese of Cologne. The manuscript remained there during the Middle Ages, but then entered a collection in Cologne. By the 18th century it was held at the Evangelical Convention in Sopron, from where in 1814 it entered the National Library.

The manuscript was identified and first analysed by two researchers, Anna Boreczky and András Németh, and by 2010, a number of foreign researchers - most notably Xavier Barral i Altet - were involved in first phases of research, the results of which were presented to the public on December 8, 2010. The present facsimile edition is the result of a international collaboration, and is accompanied by multi-language commentary. The commentary volume starts with an introduction by Ernő Marosi, and was written by Xavier Barral i Altet, Anna Boreczky, Herbert L. Kessler, András Németh, Andreas Nievergelt and Beatrice Radden Keefe. In addition to the basic data and a bilingual (English and Hungarian) description of the manuscript, a critical edition of the text is also included.

Data of the volume: Apollonius pictus. Egy illusztrált, késő antik regény 1000 körül. / An illustrated, late antique romance around 1000. Ed. Anna Boreczky and András Németh. Budapest, Széchényi National Library, 2011.

The above text is based on the information released by the National Széchényi Library. A review will follow, once I get hold of the publication. Below is one page of the fragmentary manuscript.

Sunday, January 22, 2012

Italy and Hungary in the Renaissance (Book review)

Back in 2007, a major conference was organized at Villa I Tatti (The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence), dedicated to Humanism and early Renaissance art in the Kingdom of Hungary. The conference aimed to give an overview of the field, focusing naturally on connections between Italy and Hungary. In August 2011, the long-awaited volume of the these studies has been published by Villa I Tatti, edited by Péter Farbaky and Louis A. Waldman. The conference, the research trip to Hungary which followed it, and the volume together represent the crowning achievement of the role of I Tatti as "a bridge between Hungary and Florence in the world of humanistic scholarship for three decades" - as emphasized by director Joseph Connors in the Foreword.

It also has to be pointed out that in 2008, an entire series of exhibitions and events were organized in Hungary in the framework of the so-called Renaissance Year. Three exhibitions, in particular, have to be mentioned here: the Budapest History Museum organized a large international exhibition dedicated to the rule of King Matthias in Hungary. Titled Matthias Corvinus, the King, the exhibition was accompanied by a large catalogue, also edited by Péter Farbaky with Enikő Spekner, Katalon Szende and András Végh (published in an English version as well). A large number of the participants of the 2007 Villa I Tatti conference also contributed to this catalogue - where naturally actual physical objects are in focus. The two publications thus nicely complement each other. Two smaller exhibitions focused on more special topics: the exhibition at the National Széchényi Library, titled A Star in the Raven's Shadow, was dedicated to János Vitéz, archbishop of Esztergom, and the beginnings of Hungarian Humanism in the middle of the 15th century. The exhibition of the Museum of Applied Arts - The Dowry of Beatrice - examined the origins of Italian majolica at the court of King Matthias, focusing on the magnificent Corvinus-plates made in Pesaro. (To get the English-language catalogues, search for item nos. 58713 and 113069 at www.artbooks.com).

|

| Temperance, 15th c. fresco at the Palace of Esztergom |

However, the conference organized at I Tatti was the event met with most extensive response. This was largely due to two of the the papers presented at the conference and a press conference held by the Hungarian Cultural Minister in Rome, announcing the findings of these two papers. At the conference, Zsuzsanna Wierdl and Mária Prokopp presented their theory concerning one of the 15th century frescoes at the castle of Esztergom, attributing it to the young Botticelli - a subject I have written about elsewhere on this blog.

Naturally, there is much more to the book than these sensational claims. The volume makes the lectures presented at the conference available in an edited format. The description of the book at the Harvard University Press website gives a good overview of its main topic:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)