New finds of Romanesque stone carvings were presented by the László Teleki Foundation earlier this week. The carvings were found during reconstruction work at the castle of Borosjenő (Ineu, Romania) in 2016 and 2019. The carvings most likely come from the abbey church of Dénesmonostora, which was located near the castle and was abandoned by the early 16th century. The stone carving were found in walls of the castle dating from the 1530s-1540s. These carving now provide some context from the lone capital decorated with a siren, which had been at the Hungarian National Museum since the 1870s.

The finds shine some light on the rich architecture and culture of a chain of Árpádian era monasteries established along the lower Maros river valley - an area that played a key role in the transportation of salt from Transylvania towards the plains. Perhaps Bizere is the most famous monastery in this region, which had been excavated during recent decades - and which is discussed in an important conference volume on monastic life. More recently, excavations were started at the Cistercian monastery of Egres as well. Dénesmonostora was established for the Augustinian canons, at an unknown date before 1199.

|

| Siren from Borosjenő (originally Dénesmonostora), Hungarian National Museum |

No research on the castle of Borosjenő had been carried out since it was rebuilt in the 1870. The building stood empty since 2004, and the municipality is currently working on rebuilding the castle. Already during the surveys carried out in 2016, it was discovered that the walls incorporate a large number of pre-1200 stone carvings used as building materials. At that time, 9 early carvings were recovered. In 2019, with support of the Rómer Flóris Plan, another 14 smaller or larger stones were found, and dozens more were documented within the walls. This work was carried about by Zsolt Kovács and Attila Weisz, art historians from Cluj.

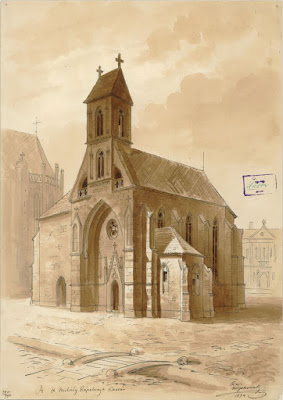

|

| Borosjenő (Ineu) castle, awaiting restoration |

The stone carvings are mainly capitals and bases of columns, decorated with various vegetal carvings in Romanesque style. They most likely date from around the middle of the 12th century, and are very important because from this region nothing similar has been found so far - now these finds can be analyzed through comparisons with carvings from such important ecclesiastiacal centers as Székesfehérvár or Pécs. The excavation of the site of the former monastery is also planned for the near future, which would certainly help place these objects in context.

A final remark: earlier this year I published a brief study on the churches of the Augustinian canons in Hungary, where Dénesmonostora was mentioned, but I could not say much about its church. As these investigations will continue, we will certainly know more about the canons regular in Hungary as well, an order which played an important role in the 12th century monastic reform in Central Europe.

A final remark: earlier this year I published a brief study on the churches of the Augustinian canons in Hungary, where Dénesmonostora was mentioned, but I could not say much about its church. As these investigations will continue, we will certainly know more about the canons regular in Hungary as well, an order which played an important role in the 12th century monastic reform in Central Europe.

Photos by Attila Mudrák, used with permission of the László Teleki Foundation.