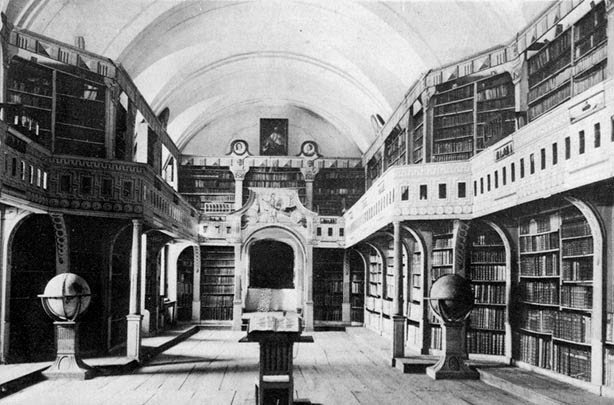

The Batthyáneum Library of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia, Romania) is one of the most important historic libraries in Transylvania. It was founded in 1798 by Ignác Batthyány, the bishop of Transylvania. The library was housed in the former church of the Trinitarian order - first an observatory was created here, and later the library was established in the building (all this was modeled on the Archdiocesan Library of Eger). The library of Batthyány grew from many sources, but the most important among these was the library of Christoph Anton von Migazzi, the bishop of Vác and also the bishop of Vienna. Batthyány bought the 8000 volume library of Migazzi, which included a lot of medieval manuscripts. When established at Gyulafehérvár, the Batthyáneum held about 20.000 volumes - a number which continued to increase throughout the 19th century. In addition to simply being a library, the institution worked as a museum, holding Batthyány's collection of minerals and naturalia, as well as a collection of ecclesiastical art. Finds from the excavations of Gyulafehérvár cathedral carried out by Béla Pósta in the early 20th century are also kept here.

The 20th century history of the library was not free from controversy: some books were sold in the 1930s, but the institution continued too function as a public library even after the Trianon peace treaty awarded Transylvania to Romania. However, in 1949 the collection was nationalized, and later became part of the Romanian National Library. Access to the collections became very limited - a situation which continues to this day. Even though a government decree returned the building and collection of the library to the Roman Catholic Archbishopric of Gyulafehérvár, the Library still functions as part of the state library system, and the court cases going on have so far not clarified the situation.

The library holds today altoghether 927 manuscripts and 565 incunabula, making it the richest collection of this kind of material in all of Romania. The medieval manuscripts are of various origins: Migazzi's library included all kinds of western manuscripts, but Batthyány also bought complete medieval libraries from Hungary, including the holdings of the ecclesiastical libraries of Lőcse (Levoča / Leutschau, Slovakia, see this Hungarian language study with German summary: Eva Selecká Mârza: A középkori Lőcsei Könyvtár, Szeged, 1997.). Several Transylvanian collections were also incorporated into the library, and there are rich holdings of orthodox Romanian manuscripts in the collection. In the framework of a European digitization project, a large number of manuscript are now available in the Manuscriptorium platform. In fact, there is a special section dedicated to manuscripts from the Batthyáneum.

The library holds a large number of first class illuminated manuscripts - many of which can now be consulted online. The following is a selection of a few of the most important of these (providing direct links to pages of this dynamic website is quite complicated. I managed to make direct links to the digital facsimile pages below - but you may start to browse or search from the start page, to get to object descriptions, etc.)

Ms II 1, first part of the Lorsch Gospels (Codex Aureus of Lorsch), from the Palace workshop of Charlemagne, dating around 810 (on the history of the whole manuscript, see also this overview)

Ms III 87, a nicely illustrated early 15th century Franco-Flemish Book of Hours

Ms II 134, A Missal from Pozsony (Bratislava / Pressburg), dating from 1377, with explicit by Henrik of Csukárd

There is a lot more there - you can start browsing from the start page, Manoscriti qui in theca batthyanyana. Furthermore, you can find some more illuminated manuscripts from the Europeana database - not all of which have been made available in the current digitization effort.