At a press conference on October 30th, 2019, the

Teleki László Foundation presented the early 15th-century fresco cycle uncovered in the Calvinist church at Visk (Vyshkovo, Ukraine). The wall paintings - which had been found in 2001 and partially revealed in 2012 - were uncovered with the support of the

Rómer Flóris Plan. This is a Hungarian government program launched in 2015 and aimed at protecting elements of Hungarian cultural heritage across the borders. The wall paintings of Visk were presented to the press by Prof. Ernő Marosi, restorer József Lángi, and myself (Zsombor Jékely).

Visk is located in the Zakarpattia Oblast region of Ukraine - and area which was part of the Kingdom of Hungary until 1918. The medieval church at Visk was built in the first third of the 14th century and is a simple Gothic edifice with a rectangular nave and a polygonal sanctuary. The town itself was one of the five royal settlements in Máramaros county, an area known for its salt mines. Nothing remains today of the medieval castle once guarding the settlement. Since the mid-16th-century, the population of Visk had converted to Calvinism, which led to the reconfiguration of the medieval church as well. In 1717, the town was burned down during the last raid of the Crimean Tatars into Hungary. When the church was rebuilt, the medieval frescoes were no longer visible - they were eventually covered by rich ornamental paintings executed in 1789.

|

| Press conference with Ernő Marosi, József Lángi and Zsombor Jékely (photo: Magyar Kurír) |

The medieval wall paintings of the church were preserved in the sanctuary. Their existence had been known for some time, and their presence under later layers of plaster was established in 2001. Several details had been uncovered by restorer József Lángi in 2012, which led to a plan for their complete recovery. Once the community of the church was also convinced of the importance of these frescoes, work could commence with the help of the Rómer Flóris Plan. In September - October 2019, the entire surface of the sanctuary wall has been cleaned and wall paintings have been uncovered on the northern and southern wall of the sanctuary, as well as around the eastern windows.

|

| Passion cycle on the northern wall of the sanctuary |

The ensemble recovered by József Lángi is fragmentary: a large Late Gothic window opened in the southern wall destroyed a large portion of the wall paintings. The vaults collapsed (most likely in 1717) and were replaced by a flat ceiling - thus a very important part of the former ensemble is missing. A 19th-century gallery installed in the sanctuary for an organ caused further damage. Despite all this, a remarkably complete cycle of wall paintings has come to light. The northern and southern wall of the sanctuary was decorated with a detailed Christological cycle, narrating the story of Christ from the Annunciation through the Passion all the way to the death and Coronation of the Virgin Mary.

|

| Massacre of the Innocents |

The cycle was arranged in four registers in a wrap-around pattern (so running left to right on the northern wall, continuing on the southern wall, then jumping back to the northern wall and so on). Many of the scene survive fairly intact, including monumental compositions of the Massacre of the Innocents and the Entry into Jerusalem, as well as several episodes from the Passion of Christ. Although there is a lot of damage to the cycle, and the fire of 1717 changed the coloring of the paintings, the power of the storytelling is still clear to see today. Dramatic and expressive scenes - such as the Arrest of Christ or the scene of Christ being nailed to the cross - add to the richness of the narrative. On the eastern walls, in the spaces between the windows, a gallery of saints was painted in several rows. Most of them appear to be female martyr saints: Catherine, Barbara, and Margaret can be identified today.

The surface of the wall paintings still needs to be cleaned and they need to be restored - a task which can hopefully be completed during the next two years. In the meantime, we can already establish that the fresco cycle was painted during the second part of the reign of King Sigismund (1387-1437) - most likely in the 1420s. No other works are known by the same workshop in the Upper Tisza Valley, so the discovery of these frescoes is a significant addition to our knowledge about medieval painting in north-eastern Hungary. Art historical research on the fresco cycle will commence in the near future, and hopefully, initial results will be published soon.

You can read more about the press conference (in Hungarian) in this overview by

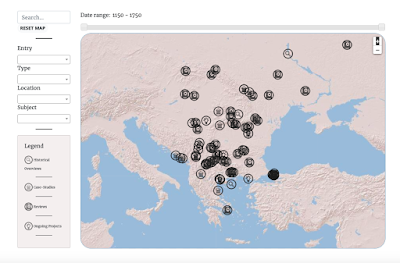

Magyar Kurír. To learn more about the medieval churches of the region, have a look at the website of the

Route of Medieval Churches. Photos in the post are by Attila Mudrák.